Ball Python heat pits are sensory organs that allow the snake to receive and interpret infrared radiation (heat). They might just look like holes in the snake’s face, but pit organs literally let Ball Pythons see heat, giving them the edge over their prey. They are even effective in complete darkness.

In this article, we’re going to learn all about these organs, from their anatomical structure to potential issues with them. But first, check out the video below of the heat pits on one of my snakes:

What are the holes on a Ball Python’s face?

I can remember the first time I saw a Ball Python up close. Apart from the fact that it was incredibly beautiful, seeing the holes that lined its jaws did seem really weird. They literally look like holes going into the tissue.

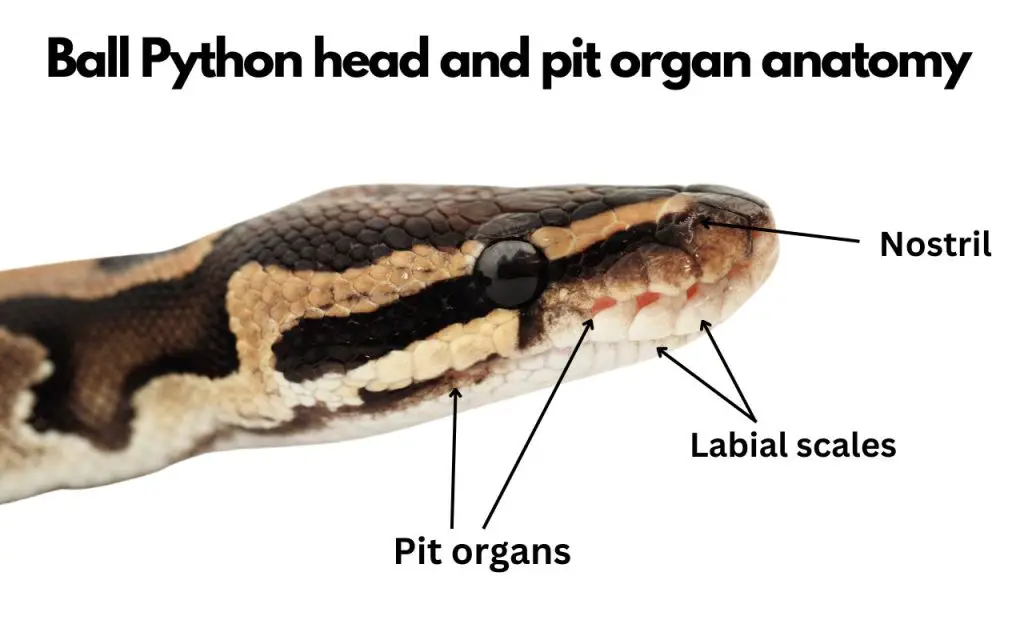

You can see about ten of these holes along the upper jaw and rostrum (nose), and about 6 along the back of the lower jaw. Unlike the tiny nostrils these snakes have, these holes look much larger.

So what are they? Well, they are essentially heat sensors. These pits are specialised organs that literally allow the snake to sense heat, in a way which is alltogether different from vision.

Rather than seeing heat, these heat pits actually give the snakes a “feeling” of where a temperature change is occurring, and how intense the change is. A warm-blooded prey item running towards the snake gives a strong feeling, and is easy to pinpoint – especially if the background is cooler. In general, it’s thought that heat pits give a reading from a distance of around 16in (40cm).

Anatomy of Ball Python Heat Pits

Before we get into it – heat pits have a few different names that people use. They include labial pits, heat-sensing pits, thermo-receptive pits, thermal pits, and pit organs.

In this article, I’m going to go with the term “pit organ” because it’s simple, and it’s the one sensory ecologists tend to use most often.

Pit organs are composed of three main parts:

- The pit – this is a recess that looks like a hole. It can be in the center of a scale, or between scales.

- The membrane – this is a veil of tissue stretched across the pit.

- An air pocket – a cavity behind the membrane.

Of these three parts the membrane is the most complex. In fact, the membrane itself has several crucial components:

- Mechanoreceptors (we think). Mechanoreceptors feel sensations like touch and heat.

- Vascular tissue. These sensory organs are highly vascularized, which may help them work more efficiently

- Nerve endings. Sensations picked up by the mechanoreceptors are fed into nerve endings that can transmit them to the brain.

How they work

As yet, scientists are not 100% certain of how pit organs work, but a study by Moiseenkova, et al. 2003, supports the idea that they do respond to a physical sensation of heat, rather than to any kind of light.

As far as we can tell, they seem to rely on thermoception, or heat sensing. The mechanoreceptor cells in the membranes receive infrared radiation (heat), then the nerve endings linked to the them carry the signal up the trigeminal nerve and into the brain.

When the signal reaches the brain, it is processed and interpreted into a feeling. The intensity of this feeling will be determined by the intensity of the signal.

So, a bigger change in temperature = a bigger feeling, and one that’s more likely to get the snake’s attention. This is very similar to how our brains process touch, heat, and cold on our skin.

It is also thought that the highly vascularized membranes might also act as a heat exchange, further sensitizing the mechanoreceptive cells. Notwithstanding, at this point it is mostly speculation.

Interestingly, pit organs use an incredible simple structural advantage to not only detect how much heat is hitting them, but where it comes from. Because they are recessed, i.e. set back from the front of the scale, heat can only hit all of the membrane if it is directly in front of it.

If heat hits the pit from the left, some of it will be obscured by the left side of the scale next to it. This means the heat will only activate a signal from the right side of the membrane inside the pit, and this will automatically tell the snake’s brain what direction it’s coming from.

Evolution of Ball Python Heat Pits

Heat pits have evolved in many different species of snake. Some of them aren’t particularly closely related, either. This is a case of convergent evolution due to common habits.

There are two families and one subfamily of snakes that have pit organs either on the labial scales or between the eye and nostril. Check out the table below:

| Classification: | Pit organ location: | Complexity: |

| Family Pythonidae (Pythons) | Labial scales | Simple |

| Family Boidae (Boas) | Labial scales | Simple |

| Family Viperidae, subfamily Crotalinae (Pitvipers) | Loreal scales (between eye and nostril) | Complex, highly evolved |

*Note: there is strong evidence that pitvipers also use pit organs for thermoregulation. It’s not been proven in Ball Pythons, but I’m going to go ahead and say it’s very likely.

Whilst pit organs are less complex in pythons and boas, they are still very effective. More to the point, they have all probably evolved in the same way.

Again, I’m saying probably because no one is 100% (even if they tell you they are!). The most likely scenario is that nocturnal snakes relied at least partially of sensing the body heat of prey that brushed up against them to strike.

This would have relied on receptors in the scales that in evolutionary terms were inherited from fish and amphibians, both of which can sense heat and touch through their skin.

Over time, the snakes with more heat sensing cells in their scales got an advantage over others, caught more prey, and reproduced more.

Eventually, this became a selective pressure which pushed the evolution of denser and denser bundles of thermoceptive cells, until they formed full-blown organs.

Importance of Ball Python heat pits in captivity

Ball pythons use a range of senses for hunting, so you need to appeal to all of these senses for feeding them. They use:

- Sight

- Smell

- Touch

- Heat

What you’ll find is that heat sense is not far behind sight when it comes to getting a Ball Python to strike. It’s particularly important to remember this when feeding frozen-thawed prey.

Personally, I leave rats out to defrost for most of the day for my snakes. This lets their scent get to them, and gradually get them interested by the time evening comes.

Then, around 8 or 9PM, I put the now defrosted rats in some very warm water, inside plastic bags. I let them heat up for around 10 minutes, or until they feel noticeably warm all the way through.

Then I dangle them in front of the snakes and BAM! Each hungry snake sees a prey item that is both moving and warm. This gets them just as interested as if I were giving them live prey.

Do scaleless Ball Pythons have heat pits?

In case you aren’t familiar, scaleless Ball Pythons are the super form of Scaleless head Ball Pythons. Scaleless head is an incomplete dominant mutation that in its super form – scaleless – creates a complete absence of scales aside from the eye caps.

In a nutshell, a scaleless Ball Python is like a highly muscular worm with a nice pattern. Personally, I’m not into scaleless snakes. I find the idea of an animal that is deformed kind of depressing. That said, there a lot of people who like them, and they are a unique-looking morph for sure.

Something you’ll notice about heat pits in Ball Pythons is that they are recessed behind neighboring labial scales. The structure that gives them a recess is generated by the scales themselves. So how does this work with scaleless Ball Pythons?

Basically, heat pits are completely absent from scaleless Ball Pythons. They just look like the surrounding skin. What a lot of keepers have noticed, however, is that these snakes do still respond to heat.

It would seem that scaleless Ball Pythons do still have the heat-sensing tissue, and it still works. It just isn’t recessed in a pit like it would be in regular snakes.

Potential issues with heat pits

Given their delicate structure, pit organs are more susceptible to injury and even infection than normal scales or skin. Let’s take a quick look at the most common issues that come up…

1. Poor shedding

If your humidity get’s too low, incomplete sheds won’t be far behind. When this occurs, it’s not uncommon for bits of skin to get stuck on the scales surrounding the pit organs and eyes.

If this is currently a problem for your snake, check out the Ball Python humidity and shedding article in the humidity, water, and shedding section of this care sheet.

2. Substrate stuck in heat pits

Ball Pythons love to push their nose into stuff, especially if they get frustrated waiting for their next meal. If you use a fine, damp substrate, it’s not uncommon for it to crammed into their pit organs.

If left in their for too long it obstructs them and could even lead to infections in the long-run. So, it seems there are two main culprits for this: coco coir (like Eco Earth), and paper mulch.

3. Nose rubbing

As I’ve just mentioned above, frustrated Ball Pythons will push their nose into things. Frustrated males get especially bad with this if they can smell females nearby.

Generally speaking, this isn’t too dangerous for the snake. If the underside of the lid to your enclosure has any sharp or pointy bits to it, then it can injure your snake’s rostrum and pit organs though.

Always inspect any enclosure thoroughly before using it and modify it if need be.

Final thoughts

Understanding pit organs is vital for understanding the feeding habits of your Ball Python. They use heat to hunt, and it appears to be one of their main senses for locating prey. Just seeing or smelling their food won’t get them striking every time.

If you feed frozen-thawed prey like most of us do these days, then you should focus on getting it warm enough to trigger the pit organs for a great feeding response.

FAQ related to Ball Python pit organs:

Let’s take a moment to answer some of the most common questions regarding heat pits. If your question isn’t covered, don’t hesitate to get in touch via the contact page.

Why do ball pythons have heat pits?

Ball Pythons have heat pits to locate warm-blooded prey in the dark. Heat pits are putatively more effective for nocturnal snakes, that enjoy either mammals or birds as food. They may also help them thermoregulate by spotting warmer or cooler places to rest.

Can Ball Pythons see in the dark?

Technically Ball Pythons cannot see in the dark. Most scientists agree that the pit organs allow pythons to accurately strike at prey in the dark, but that the images sent to the brain are not as accurate as vision. Sight encompasses fine detail and colors, both of which are thought to be absent from heat sense.

Which pythons have no heat pits?

Womas (Aspidites ramsayi) and Black Headed Pythons (Aspidites melanocephalus) both lack heat pits. This may be due to the fact that they generally prefer cold blooded prey like lizards, rather than warm-blooded prey like mammals.

Also on this topic:

- What is the best way to feed a Ball Python?

- How often should Ball Pythons eat?

- Do Ball Pythons Need Vitamin Supplements?

- Ball Python not eating (what should I do?)

- When should you assist feed a baby Ball Python?

For more on Ball Python predation:

Back to the Ball Python feeding page